25 Exchangeable beliefs

\(\DeclarePairedDelimiter{\set}{\{}{\}}\) \(\DeclarePairedDelimiter{\abs}{\lvert}{\rvert}\)

25.1 Recap

In the chapters of part Inference I we had an overview of how an agent can draw inferences and make predictions of the most general kind, expressed by general sentences, using the four fundamental rules of inference.

Then, in part Inference II, we successively narrowed our focus on more and more specialized kinds of inference, typical of engineering and data-science problems and of machine-learning algorithms. First we considered inferences about measurements and observations, then inferences about multiple instances of similar measurements and observations. The idea was that an agent can arrive at sharper degrees of belief – that is, it can learn – by using information about “similar instances”.

For these purposes we introduced a specialized language about quantities and data types in part Data I, and about “populations” of similar “units” in part Data II.

In ch. 24 we had an overview of possible types of tasks, many of which are typical of machine learning algorithms such as deep networks and random forests. We found a remarkable result: a perfect agent – one that operates according to Probability Theory – can in principle perform any and all of those tasks by using the joint probability distribution

\[ \mathrm{P}( Y_{N+1}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}y_{N+1} \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} X_{N+1}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}x_{N+1} \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}\dotsb \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} Y_{1}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}y_{1} \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} X_{1}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}x_{1} \nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{I}) \]

where \(Y\) and \(X\) are the variates of interest.

The agent only needs to do some calculations with this joint distribution, involving sums and divisions. This distribution must be specified for all possible values of \(x_{1}, \dotsc, x_{N+1}\), \(y_{1}, \dotsc, y_{N+1}\), and \(N\).

For example take the task of predicting some variates (predictands) for a new unit, from knowledge of other variates (predictors) for the same unit and of all variates for \(N\) other units. Solving this task corresponds to calculating

\[ \begin{aligned} &\mathrm{P}\bigl( {\color[RGB]{238,102,119}Y_{N+1} \mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}y_{N+1}} \pmb{\nonscript\:\big\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{}} {\color[RGB]{34,136,51}X_{N+1} \mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}x_{N+1}}\, \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}\, \color[RGB]{34,136,51}Y_N \mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}y_N \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}X_N \mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}x_N \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} \dotsb \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} Y_1 \mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}y_1 \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}X_1 \mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}x_1 \color[RGB]{0,0,0}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}{\mathsfit{I}} \bigr) \\[2ex] &\qquad{}= \frac{ \mathrm{P}\bigl( \color[RGB]{238,102,119}Y_{N+1} \mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}y_{N+1} \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} \color[RGB]{34,136,51}X_{N+1} \mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}x_{N+1} \color[RGB]{0,0,0} \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} \color[RGB]{34,136,51}Y_N \mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}y_N \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}X_N \mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}x_N \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} \dotsb \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} \color[RGB]{34,136,51}Y_1 \mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}y_1 \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}X_1 \mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}x_1 \color[RGB]{0,0,0}\pmb{\nonscript\:\big\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{}} {\mathsfit{I}} \bigr) }{ \sum_{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}y} \mathrm{P}\bigl( {\color[RGB]{238,102,119}Y_{N+1} \mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}y} \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} {\color[RGB]{34,136,51}X_{N+1} \mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}x_{N+1}} \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} \color[RGB]{34,136,51}Y_N \mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}y_N \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}X_N \mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}x_N \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} \dotsb \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} Y_1 \mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}y_1 \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}X_1 \mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}x_1 \color[RGB]{0,0,0}\pmb{\nonscript\:\big\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{}} {\mathsfit{I}} \bigr) } \end{aligned} \]

To build an AI agent that deals with these kinds of task we must:

- choose a joint distribution according to reasonable assumptions and background information,

- encode it in a computationally feasible way.

In order to reach these two goals we shall now narrow our focus further, upon inferences satisfying a condition that greatly simplifies the calculations, and that is also reasonable in many real inference problems – and it is moreover typical of many “supervised” and “unsupervised” machine-learning applications.

25.2 States of knowledge with symmetries

An agent’s degrees of belief about a particular population may satisfy a special symmetry called exchangeability. This symmetry can be understood from different points of view. Let’s start from one of these viewpoints, and then make connections with alternative ones.

Take again two populations briefly mentioned in § 20.1:

- Stock exchange

- The daily change in closing price of a stock during 1000 consecutive days. Each day the change can be positive or zero: \({\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;+;}}\), or negative: \({\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;-;}}\).

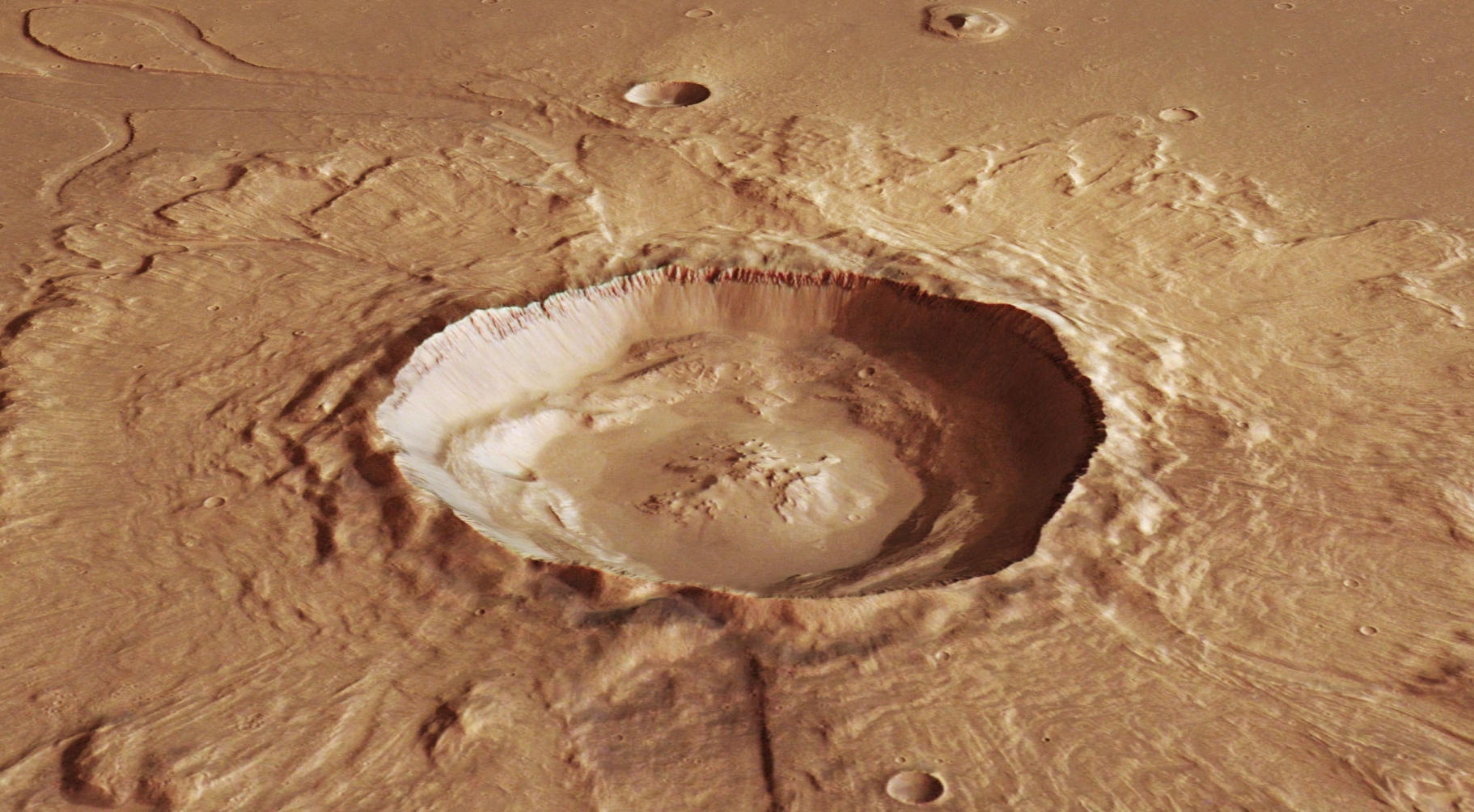

- Mars prospecting

- A collection of 1000 similar-sized rocks gathered from a specific, large crater on Mars. Each rock either contains haematite: \({\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\), or it doesn’t: \({\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\).

Suppose that, in each of these populations, you (the agent) don’t know the variate value for unit #735, and for some reason would like to infer it. You are given the variate values for 100 other units, which you can use to improve your inference. Now consider this question:

How much does the relative order of the 100 known units and the unknown unit matter to you, for drawing your inference?

We know, from information theory, that it never hurts having extra information, such as the units’ order. But you probably judge the units’ order to be much more important for your inference in the stock-exchange case than in the Mars-prospecting one. In the stock-exchange case it would be more informative to have data from units temporally close to unit #735; for example units #635–#734, or #736–#835, or #685–#734 & #736–#785, or similar ranges. But in the Mars-prospecting case you might find it acceptable if the 100 known units were picked up in some unsystematic way from the catalogue of remaining 999 units. There are reasons, boiling down to physics, behind this kind of judgement.

The question above could also be replaced by others, slightly different but still connected to the same issue. For example:

How strongly would you like to be able to choose which 100 units you can have data from, in order to draw your inference?

or

How much would you be upset if the original order of the population units were destroyed by accidental shuffling?

or

Would it be acceptable to you if only the frequencies of the values (\(\set{{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;+;}},{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;-;}}}\) in one case, \(\set{{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}},{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}}\) in the other) for the 100 known units were given to you?

Find examples of populations where the units have some kind of ordering that you think would be very important for drawing inferences about some units, given other units. Examine why you judge such ordering to be important. (The ordering doesn’t need to be one-dimensional. For instance, the pixel intensities of an image also have a two-dimensional relative order or position: is that important if you want to draw inferences about the intensities of some pixels from those of other pixels?)

Find examples of populations where any potential ordering of the units would not be very important for drawing inferences about some units, given other units. Or, put it otherwise, you wouldn’t be excessively upset or worried if such order were lost owing to accidental shuffling of the units.

Many kinds of inference considered in data science and engineering, and all inferences done with “supervised” or “unsupervised” machine-learning algorithms, are examples where any ordering of the data used for learning is deemed irrelevant and is, in fact, often lost. This irrelevance is clear from the data-shuffling involved in many procedures that accompany these algorithms.

We shall thus restrict our attention to situations and kinds of background information where this judgement of irrelevance is considered appropriate. In reality this is not a black-or-white situation: it is possible that some kind of ordering information would improve our inferences; what we are assuming here is that this improvement is so small that it can be neglected altogether.

25.3 Exchangeable probability distributions

Let’s take the Mars-prospecting problem as a concrete example. Denote by \(H\) the variate expressing haematite presence, with domain \(\set{{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}, {\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}}\).

If an agent’s background information or assumption \(\mathsfit{I}\) says that the relative order of units – rocks in this case – is irrelevant for inferences about other units, then it means that a probability such as

\[ \mathrm{P}(R_{735}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} R_{734}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} R_{733}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} R_{732}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} R_{731}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} R_{730}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} \mathsfit{I}) \]

must be equal to the probability

\[ \mathrm{P}(R_{735}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} R_{87}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} R_{7}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} R_{16}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} R_{52}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} R_{988}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} \mathsfit{I}) \]

and in fact to any probability like

\[ \mathrm{P}(R_{i}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} R_{j}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} R_{k}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} R_{l}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} R_{m}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} R_{n}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} \mathsfit{I}) \]

for instance

\[ \mathrm{P}(R_{356}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} R_{952}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} R_{103}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} R_{69}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} R_{740}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} R_{679}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} \mathsfit{I}) \]

where \(i\), \(j\), and so on are different but otherwise arbitrary indices.

In other words, the probability depends on whether we are inferring \({\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\) or \({\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\), and on how many \({\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\) and \({\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\) appear in the conditional; in the example above, three \({\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\) and two \({\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\). This property should also apply if the agent makes inferences about more than one unit, conditional on any number of units. It can be proven that this property is equivalent, in our present example, to this general requirement:

The value of a joint probability such as

\[\mathrm{P}(R_{\scriptscriptstyle\dotso}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}\ \dotso\ \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} R_{\scriptscriptstyle\dotso}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}\ \dotso \nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{I}) \]

depends only on the total number of \({\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\) values and total number of \({\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\) values that appear in it, or, equivalently, on the absolute frequencies of the values that appear in it.

Leaving the Mars-specific example and generalizing, we can define the following property, called exchangeability:

Let’s see a couple more examples.

Don’t forget that

\(\mathrm{P}(X\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}x \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}Y\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}y \nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{I})\)

and

\(\mathrm{P}(Y\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}y \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}X\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}x \nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{I})\)

mean exactly the same, because and (symbol “\(,\)”) is commutative!

Consider an infinite population with variate \(Y\) having domain \(\set{{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;low;}},{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;medium;}},{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;high;}}}\). If the background information \(\mathsfit{J}\) guarantees exchangeability, then these three joint probabilities must have the same value:

\[\begin{aligned} &\quad\mathrm{P}( Y_{3}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;high;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} Y_{4}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;low;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} Y_{5}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;medium;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} Y_{6}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;low;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{J} ) \\[2ex] &=\mathrm{P}( Y_{6}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;medium;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} Y_{5}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;high;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} Y_{3}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;low;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} Y_{4}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;low;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{J} ) \\[2ex] &=\mathrm{P}( Y_{283}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;high;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} Y_{91}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;low;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} Y_{72}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;medium;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} Y_{1838}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;low;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{J} ) \end{aligned} \]

because they all have one \({\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;high;}}\), one \({\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;medium;}}\), two \({\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;low;}}\). The same is true for these two probabilities:

\[\begin{aligned} &\quad\mathrm{P}( Y_{99}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;medium;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} Y_{1}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;medium;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} Y_{3024}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;low;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{J} ) \\[2ex] &=\mathrm{P}( Y_{26}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;medium;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} Y_{611}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;low;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu} Y_{78}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;medium;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{J} ) \end{aligned} \]

because both have zero \({\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;high;}}\), two \({\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;medium;}}\), one \({\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;low;}}\).

Consider an infinite population with variates \((U,V)\) having joint domain \(\set{{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;fail;}},{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;pass;}}} \times \set{{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}-1}, {\color[RGB]{119,119,119}0}, {\color[RGB]{204,187,68}1}}\) (six possible joint values). If the background information \(\mathsfit{K}\) guarantees exchangeability, then these two joint probabilities must have the same value:

\[\begin{aligned} &\quad\mathrm{P}( U_{14}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;pass;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}V_{14}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}1}\ \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}\ U_{337}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;pass;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}V_{337}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}-1}\ \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}\ U_{8}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;fail;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}V_{8}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{119,119,119}0}\ \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}\ U_{43}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;fail;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}V_{43}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}-1}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}{} \\ &\qquad\qquad\qquad\quad U_{825}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;pass;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}V_{825}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}-1}\ \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}\ U_{66}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;pass;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}V_{66}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}-1}\ \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}\ U_{700}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;fail;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}V_{700}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{119,119,119}0} \nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{K}) \\[3ex] &=\mathrm{P}( U_{421}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;pass;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}V_{421}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}-1}\ \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}\ U_{55}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;fail;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}V_{55}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{119,119,119}0}\ \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}\ U_{43}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;pass;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}V_{43}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}1}\ \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}\ U_{14}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;fail;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}V_{14}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}-1}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}{} \\ &\qquad\qquad\qquad\quad U_{928}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;pass;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}V_{928}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}-1}\ \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}\ U_{700}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;fail;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}V_{700}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{119,119,119}0}\ \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}\ U_{39}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;pass;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}V_{39}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}-1} \nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{K}) \end{aligned} \]

because both have: one \(({\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;fail;}},{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}-1})\), two \(({\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;fail;}},{\color[RGB]{119,119,119}0})\), zero \(({\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;fail;}},{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}1})\), three \(({\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;pass;}},{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}-1})\), zero \(({\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;pass;}},{\color[RGB]{119,119,119}0})\), one \(({\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;pass;}},{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}1})\). From this example, note that it’s important to count the occurrences of the joint values, not of the values of the single variates independently.

First let’s check that you haven’t forgotten the basics about connectives (§ 6.4), Boolean algebra § 9.1), and the four fundamental rules of inference (§ 8.5):

How much is \(\mathrm{P}(Y_4\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;low;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} Y_4\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;low;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}\mathsfit{J})\) ?

Simplify the probability

\[\mathrm{P}(X_{9}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}X_{28}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}X_{2}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}X_{28}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{I})\]

what are the absolute frequencies of the values \({\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\) and \({\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\) among the units in the probability above?

For each collection of probabilities below (the sentences \(\mathsfit{I'}, \mathsfit{I''}, \mathsfit{J'}\dotsc\) indicate different states of knowledge), say whether they cannot come from an exchangeable probability distribution, or if they might (to guarantee exchangeability, one has to check an infinite number of inequalities, so we can’t be sure about it unless they give us a general formula for the joint probabilities):

\(\begin{aligned}[c] &\mathrm{P}(C_{2}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}-1 \nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{I'}) = 31.6\% \\ &\mathrm{P}(C_{7}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}-1\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{I'}) = 24.8\% \end{aligned}\)

\(\begin{aligned}[c] &\mathrm{P}(Z_{2}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;off;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}Z_{53}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;on;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{I''}) = 9.7\% \\ &\mathrm{P}(Z_{3904}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;on;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}Z_{29}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;off;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{I''}) = 9.7\% \end{aligned}\)

\(\begin{aligned}[c] &\mathrm{P}(A_{1}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}A_{87}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}A_{3}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{J'}) = 6.2\% \\ &\mathrm{P}(A_{99}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}A_{10}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}A_{13}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{J'}) = 8.9\% \end{aligned}\)

\(\begin{aligned}[c] &\mathrm{P}(W_{4}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;-;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}W_{97}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;+;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}W_{300}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;-;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{J''}) = 6.2\% \\ &\mathrm{P}(W_{1}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;-;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}W_{86}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;-;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}W_{107}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;-;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{J''}) = 8.9\% \end{aligned}\)

\(\begin{aligned}[c] &\mathrm{P}(B_{1190}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;+;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}B_{1152}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;-;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}B_{233}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;-;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{K'}) = 7.5\% \\ &\mathrm{P}(B_{1185}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;+;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}B_{424}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;-;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}B_{424}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;-;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{K'}) = 12.3\% \end{aligned}\)

\(\begin{aligned}[c] &\mathrm{P}(S_{21}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;+;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}T_{21}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;low;}}\ \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}\ S_{33}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;-;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}T_{33}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;high;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{K''}) = 5.0\% \\ &\mathrm{P}(S_{5}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;-;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}T_{5}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{238,102,119}{\small\verb;low;}}\ \mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}\ S_{102}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;+;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}T_{102}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{34,136,51}{\small\verb;high;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{K''}) = 2.9\% \end{aligned}\)

Further constraints

The exchangeability property greatly reduces the number of probabilities that an agent needs to specify. For a population with a binary variate, a joint probability distribution for 1000 units would require the specification of around \(2^{1000} \approx 10^{300}\) probabilities. But if this distribution is exchangeable, only \(1000\) probabilities need to be specified (the absolute frequency of one of the two values, ranging between 0 and 1000; minus one because of normalization).1

1 For the general case of a variate with \(n\) values, and \(k\) units, the number of independent probabilities is \(\binom{n+k-1}{k}\).

Moreover, the exchangeable joint distributions for different numbers of units satisfy additional restrictions, owing to the fact that each of them is the marginal distribution of all distributions with a larger number of units. In the Mars-prospecting case, for instance, if \(\mathrm{P}(R_{1}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{}\mathsfit{I})\) is the degree of belief that rock #1 contains haematite, we must also have

\[ \begin{aligned} \mathrm{P}(R_{1}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{}\mathsfit{I}) &=\mathrm{P}(R_{a}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{}\mathsfit{I}) \\ &= \mathrm{P}(R_{a}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}R_{b}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{I}) + \mathrm{P}(R_{a}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}R_{b}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{I}) \end{aligned} \]

for any two different units #\(a\) and #\(b\). Therefore, if the agent has specified \(\mathrm{P}(R_{1}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{}\mathsfit{I})\), then three of these four probabilities

\[ \begin{gathered} \mathrm{P}(R_{a}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}R_{b}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{I})\qquad \mathrm{P}(R_{a}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}R_{b}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{I})\\[1ex] \mathrm{P}(R_{a}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}R_{b}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{I})\qquad \mathrm{P}(R_{a}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}R_{b}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{} \mathsfit{I}) \end{gathered} \]

are completely determined if we specify just one of them.

Assume that the state of knowledge \(\mathsfit{I}\) implies exchangeability, and a population has binary variate \(R\in \set{{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}},{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}}\).

If

\[\mathrm{P}(R_{1}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{}\mathsfit{I}) = 0.75 \qquad \mathrm{P}(R_{4}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}R_{9}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{}\mathsfit{I}) = 0.60\]

Then how much are the probabilities

\[\mathrm{P}(R_{15}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{102,204,238}{\small\verb;Y;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}R_{3}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{}\mathsfit{I}) = \mathord{?} \qquad \mathrm{P}(R_{7}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\mathbin{\mkern-0.5mu,\mkern-0.5mu}R_{11}\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}{\color[RGB]{204,187,68}{\small\verb;N;}}\nonscript\:\vert\nonscript\:\mathopen{}\mathsfit{I}) = \mathord{?}\]