“Representative” and biased samples

If samples from a population are used as conditional information to calculate probabilities about other units, then they should of course be “relevant”, in some sense (not the technical sense of chapter 18), for the inference. The very definition of statistical population (§ 20.2) is meant to have such a relevance built-in: the “similarity” of the units makes each of them relevant for inferences about any other.

Still, the procedure with which samples are selected from a population may lead to quirky and unreasonable inferences. For instance suppose we are interested in prognosing a disease for a person from a particular population, having observed a sample of people from the same population. If the sample was chosen to consist only of people having the disease, then it is obviously meaningless for our inference.

The specific problem in this example is that our inference is based on guessing a frequency distribution in the full population (as we’ll see more in detail in later chapters), but the sample, owing to the way it was chosen, cannot show a frequency distribution similar to the full-population frequency distribution.

A sampling procedure may generate a sample that is pointless for some inferences, but still useful for others.

In the inference and decision problems under our focus we would like to use a sample for which particular frequencies – most often the full joint frequency – don’t differ very much from those in the full population. We’ll informally call this a “representative sample”. This is a difficult notion; the International Organization for Standardization for instance warns (item 3.1.14):

The notion of representative sample is fraught with controversy, with some survey practitioners rejecting the term altogether.

In many cases it is impossible for a sample of given size to be fully “representative”:

Consider the following population of 16 units, with four binary variates \(W,X,Y,Z\), each with values \(0\) and \(1\):

The joint variate \((W,X,Y,Z)\) has 16 possible values, from \((0,0,0,0)\) to \((1,1,1,1)\). Each of these values appear exactly once in the population, so it has frequency \(1/16\). The marginal frequency distribution for each binary variate is also uniform, with frequencies of 50% for both \(0\) and \(1\).

- Extract a representative sample of size four units. In particular, the marginal frequency distributions of the four variates should be as close to 50%/50% as possible.

Luckily, the probability calculus allows an agent to draw inferences also when the sample is too small to correctly reflect full-population frequencies, if appropriate background information is provided.

Obviously we cannot expect a population sample to exactly reflect all frequency distributions – joint, marginal, conditional – of the original population; some discrepancy is to be expected. How much discrepancy should be allowed? And what is the minimal size for a sample not to exceed such discrepancy?

Information Theory, briefly mentioned in chapter 18, can give reasonable answers to these questions. Let us summarize some examples here.

First we need to introduce the Shannon entropy of a discrete frequency distribution. It is defined in a way analogous to the Shannon entropy for a discrete probability distribution, discussed in § 18.5. Lets say the distribution is \(\boldsymbol{f} \coloneqq(f_1,f_2, \dotsc)\). Its Shannon entropy \(\mathrm{H}(\boldsymbol{f})\) is

\[

\mathrm{H}(\boldsymbol{f}) \coloneqq-\sum_{i} f_i\ \log_2 f_i

\qquad\text{\color[RGB]{119,119,119}\small(with \(0\cdot\log 0 \coloneqq 0\))}

\]

and is measured in shannons when the base of the logarithm is 2.

If we have a population with joint frequency distribution \(\boldsymbol{f}\), then a representative sample from it must have at least size

\[

2^{\mathrm{H}(\boldsymbol{f})} \equiv

\frac{1}{{f_1}^{f_1}\cdot {f_2}^{f_2}\cdot {f_3}^{f_3}\cdot \dotsb}

\]

This particular number has important practical consequences; for example it is related to the maximum rate at which a communication channel can send symbols (which can be considered as values of a variate) with an error as low as we please.

Calculate the Shannon entropy of the joint frequency distribution for the four-bit population of table 23.2.

Calculate the minimum representative-sample size according to the Shannon-entropy formula. Is the result intuitive?

If we are only interested in a smaller number of variates of a population, then the representative sample can be smaller as well: its size would be given by the entropy of the corresponding marginal frequency distribution of the variates of interest. In the example of table 23.2, if we are only interested in the variate \(X\), then any sample consisting of two units, one having \(X\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}0\) and the other having \(X\mathclose{}\mathord{\nonscript\mkern 0mu\textrm{\small=}\nonscript\mkern 0mu}\mathopen{}1\), would be a representative sample of the marginal frequency distribution \(f(X)\).

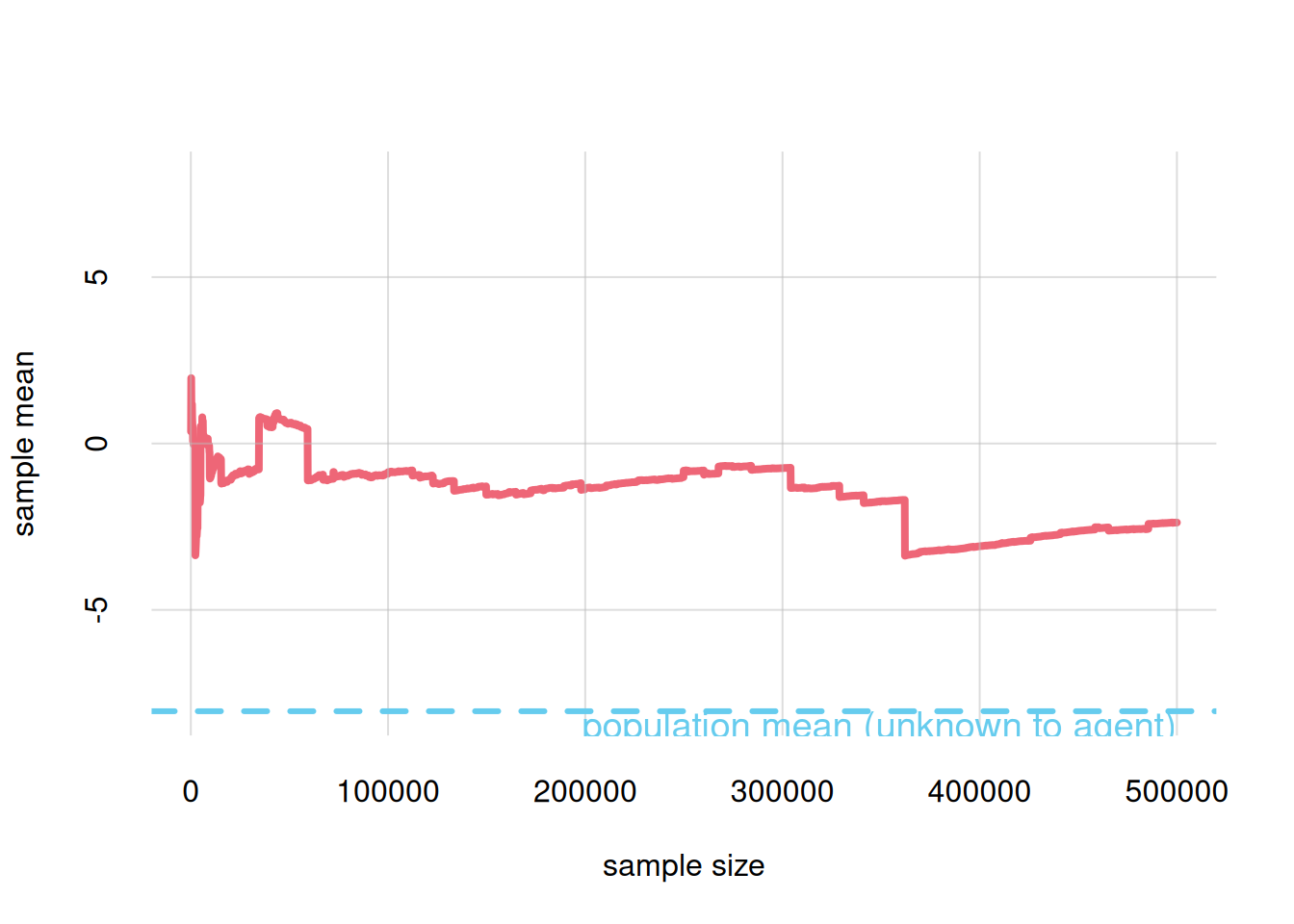

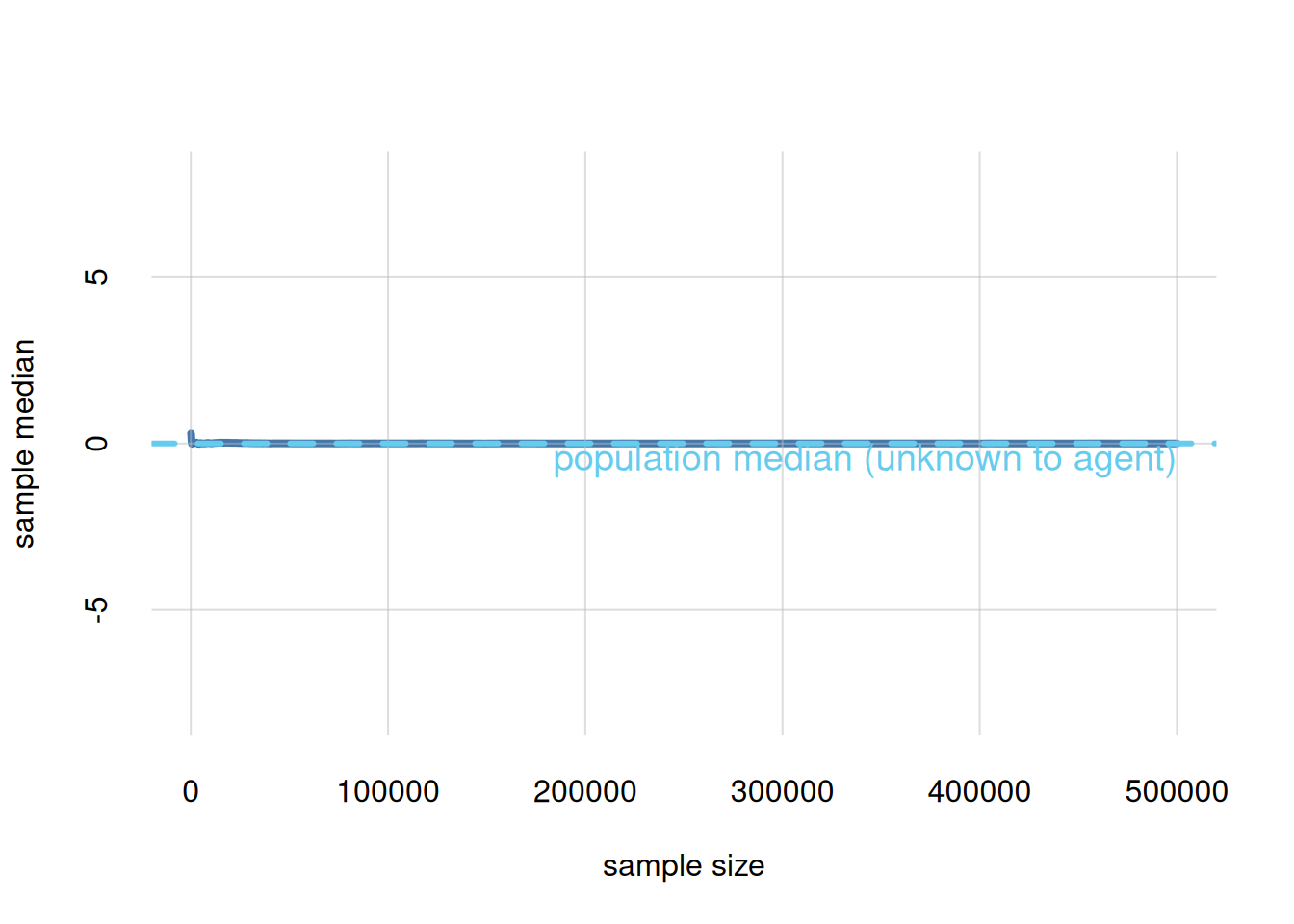

A sample that presents some aspects, such as frequency distributions, which are at variance with the original population, is sometimes called biased. This term is used in many different ways by different authors. Unfortunately, most samples are “biased” in this sense.

The only way to counteract the misleading information given by a biased sample is to specify appropriate background information, which comes not from data samples but from a general meta-analysis, often based on physical, medical, and similar principles, of the problem and population.